What is Mastering for Jazz Music?

Quick Answer

Mastering for Jazz music involves a unique mastering process in which the typical processing used, is scaled down in favor of preserving the natural sound of the original recording. The key aspects of mastering for jazz music is preserving transients and maintaining a balanced frequency spectrum.

Mastering for Jazz Music in Detail

Chances are, if you’re reading this you either love mastering music, or you love jazz - or perhaps both! If this is the case, you are most likely familiar with how typical mastering works, and the processing it imparts on a signal.

Mastering includes many forms of processing, that are scaled back and made more subtle when mastering Jazz.

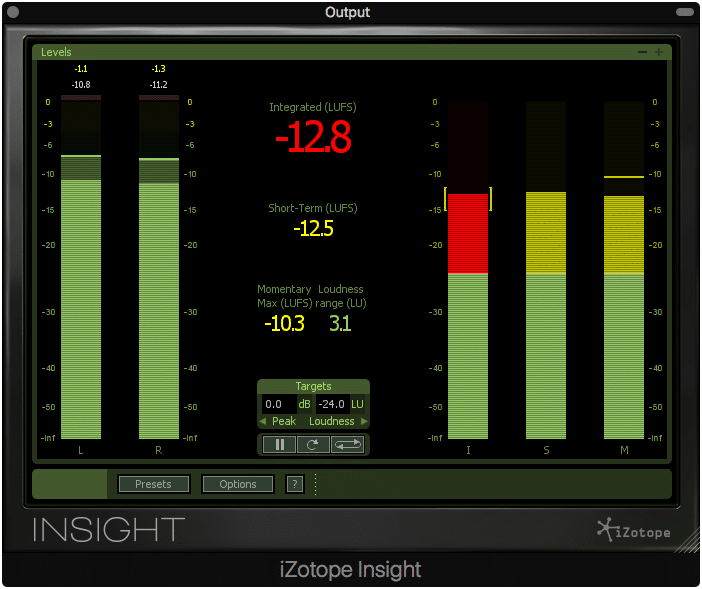

Typically speaking, mastering includes controlling the dynamics of a mix, so that it can be made louder and, in turn, compete with other tracks being released. Although this process has settled down a bit, and loudness is no longer as important as it once was, many masters still loose dynamics for the sake of loudness.

Masters used to be made louder than they are today. When it comes to Jazz, dynamics are more important to overall loudness.

This, as you can imagine, has particular effects on the sound source in general. The primary, of course, is that dynamics are lost, and so are transients - but the second may be less obvious.

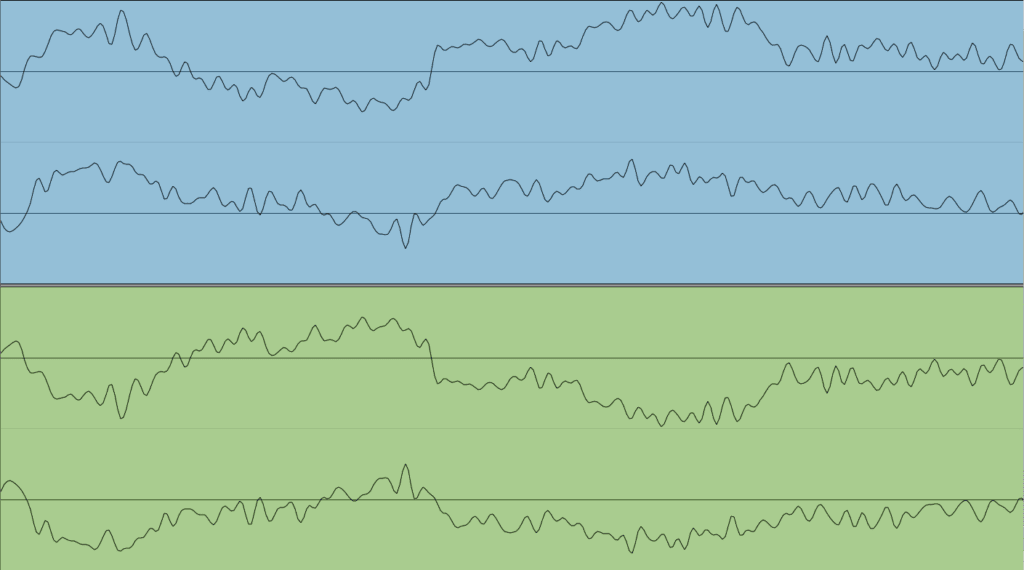

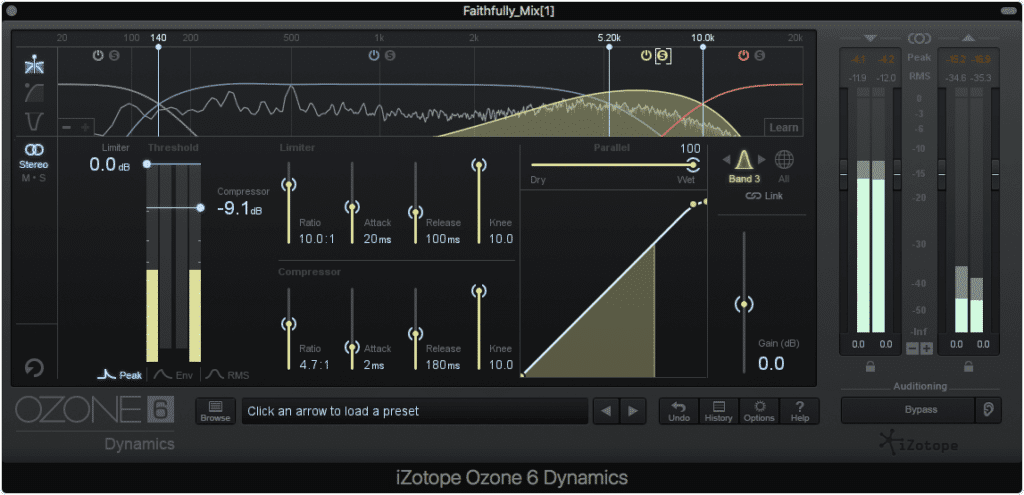

Compression can heavily affect the dynamics of a mix or master.

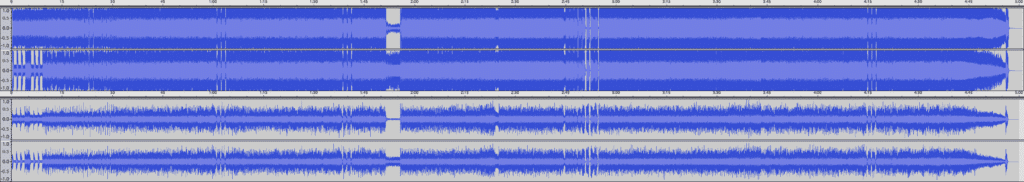

Essentially, whenever a mix is made into a loud master, quieter more nuanced aspects of the recording are made to be almost as loud as what was once the loudest aspects . This happens with any form of significant compression, as peaks are attenuated, and the entire signal is made louder.

Notice how when the peaks are attenuated, and the signal is made louder, quieter parts of the master become louder, and nearly match the volume of the previously loudest dynamics. When mastering Jazz, this type of processing should be avoided.

What this results in is a “hyped’ sound - one that lacks in dynamics as we discussed, but also sounds large, processed, and somewhat “in your face. Furthermore, this results in masking or a blurring of the instruments in a recording.

Masking is a form of phase cancellation, that occurs when multiple frequencies are competing for space. When compression is used heavily, this masking can and often does become worse.

As you can imagine, this is not the sound that jazz musicians are seeking, as their intention is to portray an accurate performance - not to make the recording sound unrealistic or hyped.

The purpose of a jazz recording is to accurately portray the performance, not to create something that sounds over-processed.

With that said, we’ll be looking into these points in greater detail, including how you would most likely implement compression when mastering jazz music. We’ll also be delving into some of the other forms of processing that you may want to avoid when mastering jazz, as well as what processing might suit the genre well.

If at any point you’d like to hear how your jazz mix would sound mastered with these particular principles in mind, you can send it to us here:

We’ll master it using solely analog equipment, and send you a free mastered sample for you to review before committing to anything.

How to Apply Compression When Mastering Jazz

Considering compression can be a big part of mastering, let's delve into how it is typically used during a jazz mastering session. In short, ideally, compression isn’t needed and won’t be used during mastering.

Ideally, compression is not needed when mastering a jazz record.

Just like a limiter, a compressor will hopefully not be needed during a jazz mastering session, and if it is, it should be used sparingly. The only thing a compressor should be used for when mastering a jazz record is to protect against sudden large jumps in amplitude.

A compressor can be used to protect against sudden jumps in amplitude, but keep in mind, these may be intentional.

But, considering that in jazz, this type of jump may be intentional, a mastering engineer will need to use his or her discretion when deciding when compression is necessary. Furthermore, the dynamics of the record will most likely not be so extreme that they necessitate a limiter.

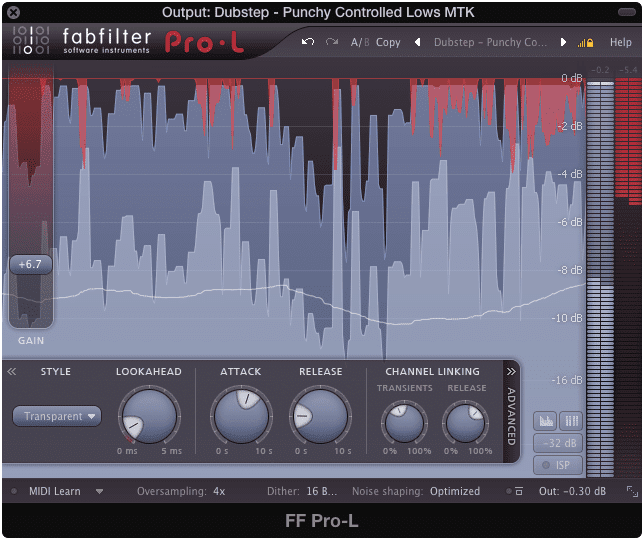

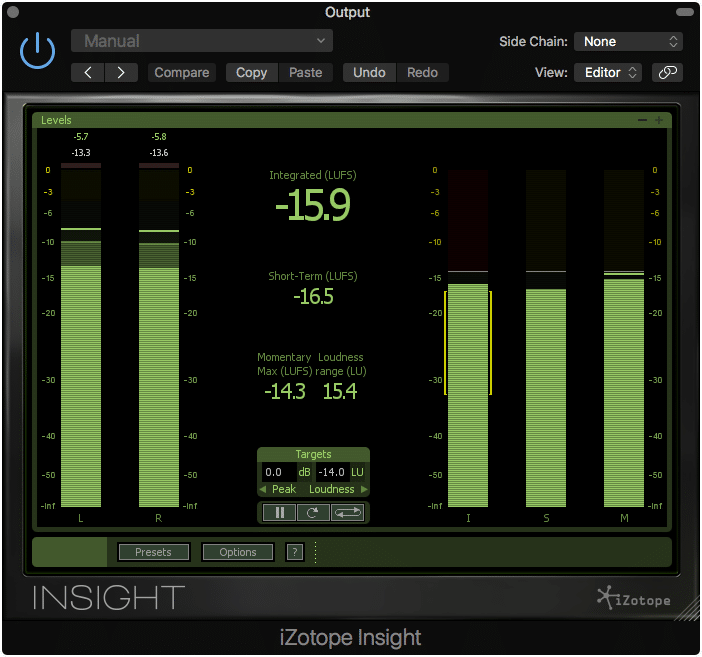

Typically, a limiter is used for the sake of pushing a signal into a greater loudness without clipping distortion occurring; however, because this loudness doesn’t need to be achieved when mastering a jazz record, using a limiter will most likely not be necessary.

A Jazz record will not need to be mastered as loud.

If a compressor is needed, and you’d like to know how to best use it to retain dynamics, I’d highly recommend checking out our blog post on the topic:

It goes into great detail about how to revere dynamics and transients during mastering, and why certain compressor settings allow this to be possible.

But for the sake of convenience, let’s review how to accomplish this here.

If you need to use compression during a jazz mastering session, there are certain settings that will ensure you maintain both transients and dynamics while keeping compression to an absolute minimum.

The general idea is to keep the attack time longer , the release time shorter , while using a moderate ratio, and setting the threshold high enough only compress during particularly dynamic sections.

But let’s look at this step-by-step.

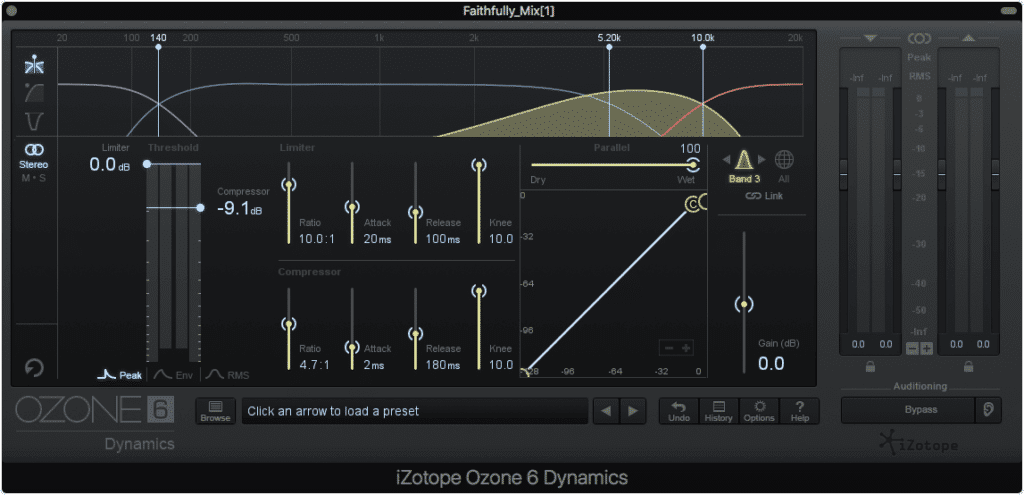

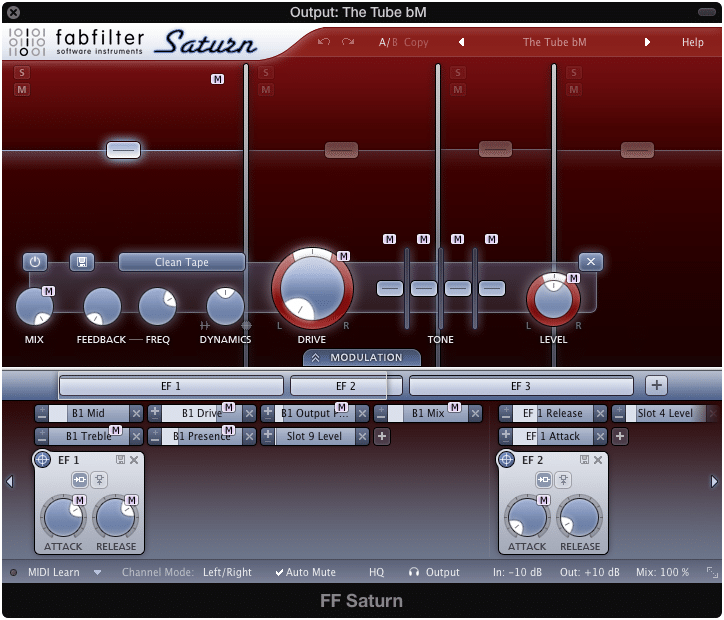

Step 1: Use a multi-band compressor to ensure that you are only compressing where needed.

Multiband compressors allow for greater flexibility.

Step 2: Check to see which band it exhibiting the excessively loud passage or dynamic.

With a multiband compressor, you can select the exact band to affect the desired frequencies.

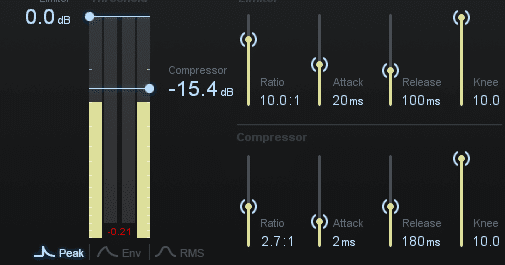

Step 3: On that band and that band only, set a ratio of greater than 1:1 but no greater than 3:1, and lower the threshold while observing your gain reduction meter. The gain should only be reduced during that particularly loud dynamic and at no other point.

Adjusting the band's ratio, and threshold can be difficult to finesse if you only want to compress one dynamic.

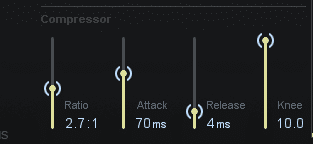

Step 4: With that section in mind, increase that band’s attack time, and decrease its release time. Ideally, the loud portion in question is reduced quickly and in a manner that doesn’t any coloration or noticeable change other than the gain reduction.

A slower attack and quicker release results in less overall compression.

If you follow these steps you should be able to accomplish compression that only compresses the section you want to compress, and doesn’t add any noticeable or audible change to the song, other than the amplitude attenuation.

Side note:If the dynamic you want to compress occupies a frequency lower than 150Hz, set your release time to no shorter than 20ms.A release time of less than 20ms when compressing lower frequencies can result in waveform distortion.

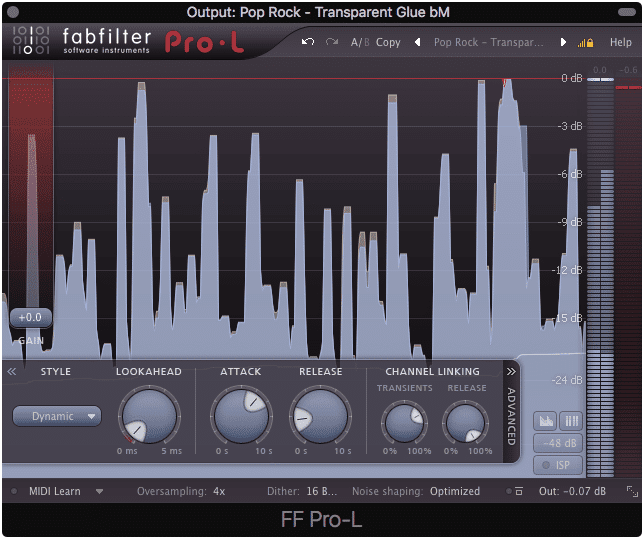

An alternative option is to not use a multi-band compressor, but instead, use a limiter with similar attack and release times.

Keep in mind that the type of compression used with a limiter will be much more harsh, as it is brick-wall limiting, but if the alternative to truncating one dynamic is noticeable compression with the multi-band compressor, limiting the one peak may be the better option.

Alternatively, a limiter can be used to set a ceiling for the recording. Keep in mind that this will cause the truncation of your dynamics.

Again, adjust your limiter’s attack and release times. If you’re using a limiter like the Waves L2 that doesn’t include these functions, it will be best to switch to a limiter that does.

How to Apply Distortion When Mastering Jazz

Your initial reaction to distortion when it comes to mastering jazz music would be not to use it in any way during the mastering process; however,a little bit of distortion in the form of harmonic generation can pleasantly accent certain elements of the instrumentation, and if present, the vocal.

Granted, adding these harmonics will need to be done in a subtle way, otherwise, they may make the master sound too present and artificially processed.

Pop and Rock records typically receive more harmonic generation, as listeners have grown to appreciate the sound of more processed recordings.

Again adding a fair amount of harmonic distortion can work well in rock, pop, and other genres in which a loud and forthright sound is expected, but in the more subtle and nuanced genre of jazz, they don’t add to but detract from the listening experience.

So, How Do You Add Harmonic Distortion?

If you’re working in a digital domain the easiest and quickest way to add harmonic generation or distortion is to use an analog emulation plugin and insert it on the desired track. These plugins have grown in popularity over the years, due to the sought-after sound of analog processing.

Many plugins emulate analog hardware, and in turn, generate harmonics.

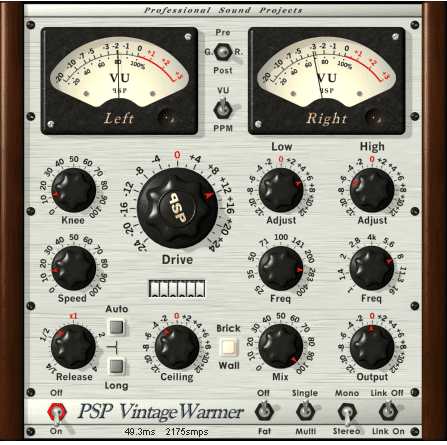

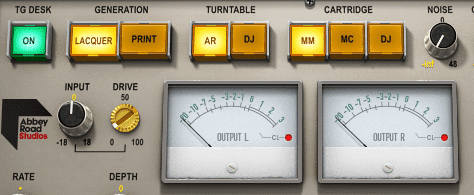

If you are to use these plugins, you may notice a “drive” function, often presented in the form of a rotary knob. It’s best to keep this at a lower setting. in fact, sometimes plugins implement harmonic generation innately, without the need to enable a setting.

Notice the drive rotary. Typically, increasing the drive function of a harmonic emulation plugin results in more harmonics or louder harmonics.

This is something to be careful of, as using multiple plugins of this nature can lead to a heavily distorted sound that doesn’t suit jazz well.

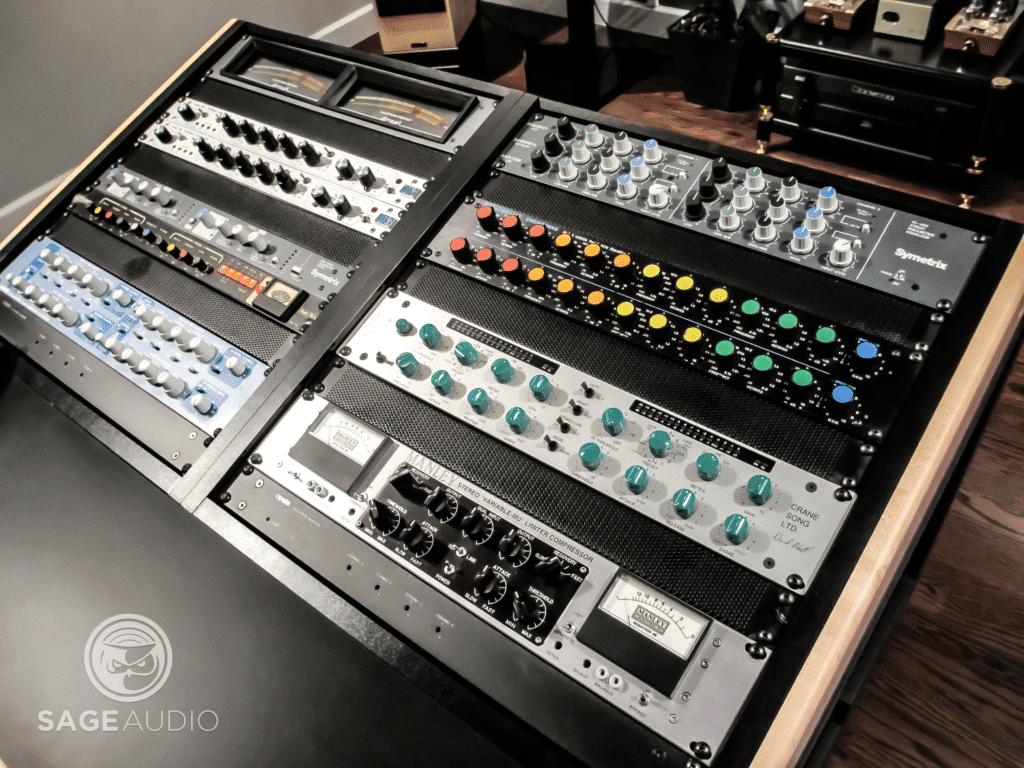

If you’re mastering with analog equipment, adding these harmonics will occur naturally during the mastering process. The very act of running a signal through analog hardware causes small harmonics to generate.

During analog mastering, harmonics occur by simply running the signal through analog equipment.

These harmonics shouldn't become too noticeable unless the signal is driven, resulting in saturation and subsequent distortion. However, if you’re mastering a jazz record, odds are you won’t be driving your signal - so this won’t be something you need to be too concerned about.

How Do You Measure Harmonic Distortion?

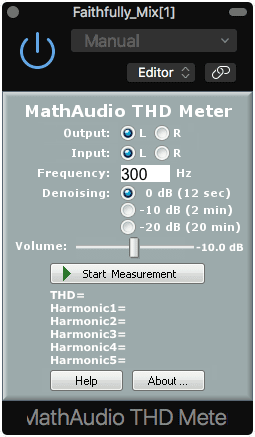

When trying to keep harmonic distortion to a minimum, it would be incredibly convenient if we could easily measure it. Unfortunately, there is no easy way to measure harmonic distortion, nor is there a plugin that offers this capability - at least not one that measures the signal’s THD.

This plugin can measure the THD of your sound card, but not your processed signal.

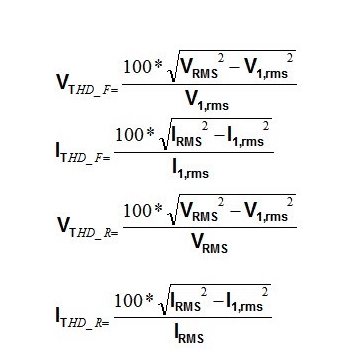

The only way to measure the THD of a signal is to compare the harmonics generated to the original signal or the fundamental. Doing so takes a somewhat complex formula and the ability to measure your signal in amps.

Here is one variation of the formula used to determine THD.

Since this would take a fair amount of time, it’s best to just use your ears and your discretion when choosing how much distortion you should add to your signal. Again keep in mind that jazz is not, nor has it ever been significantly distorted.

Since measuring your harmonics and your fundamental would take a fair amount of time, it might be best to simply use your best judgment.

With that said, it best to keep harmonic distortion to a minimum. This means avoiding harmonic exciters and limiting analog emulation plugins.

If you want to know more about distortion, particularly harmonic generation, check out our blog post that details that topic:

It’s full of great information both on analog mastering, and the harmonic generation we’ve been discussing.

Or, if you’d simply like to hear your music with some of these harmonics added in, send us one your mixes here:

We’ll master it for you and send you a free mastered sample.

How to Apply Equalization When Mastering Jazz

When applying equalization during a jazz mastering session, you want to balance the frequency spectrum, but not so much that it becomes noticeable. When applying equalization to a jazz master, be sure to use it sparingly - even more so than you would when mastering another genre.

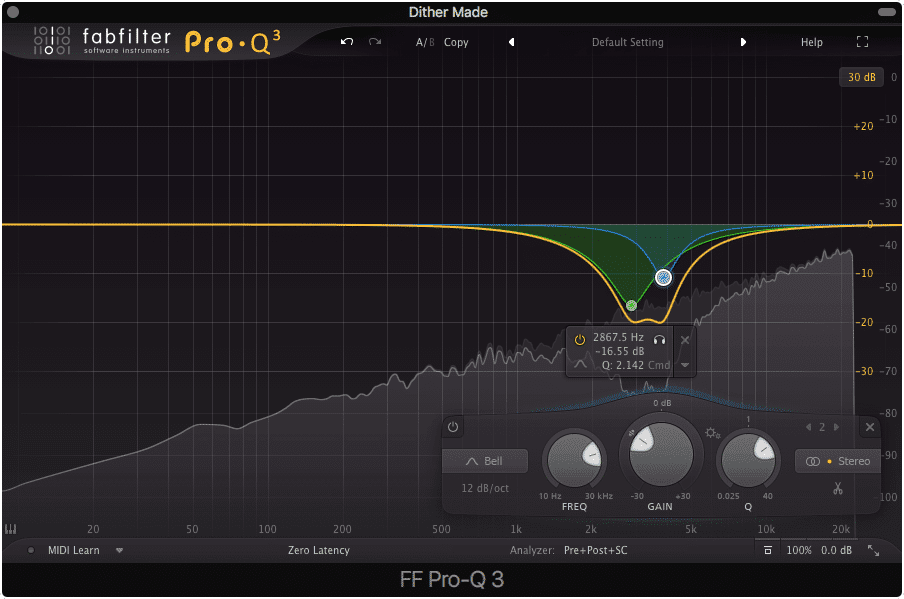

Any equalization you use during a Jazz mastering session needs to be subtle.

Granted, when mastering, you never want to add equalization in the same way you might during mixing. In mixing, it’s easier to get away with making drastic changes to the frequency spectrum of an instrument, but when mastering, even small changes can make a big difference.

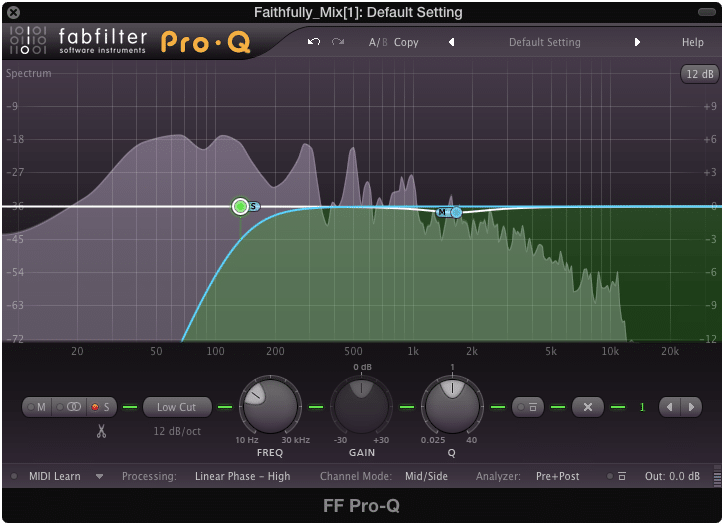

This is an example of extreme equalization, that would ruin any jazz master.

This is especially true when mastering jazz, as the primary intention of a jazz recording is to capture and retain the original sound and feel of the performance. Excessive equalization will do the opposite , as it emphasizes instruments and instrument groups that were not intended to be emphasized.

For example, say you were to amplify 10kHz on the side channel using a mid-side equalizer. Typically, this would sound great for most genres, as it would increase the width of the stereo image, and brighten the mix, particularly the instruments that occupied 10kHz and the surrounding bandwidth.

If you were to boost 10kHz, you'd most likely increase the cymbals of the drum kit. This can be beneficial if done so sparingly.

But, when mastering jazz, this type of processing would have to be kept to a minimum. It may still have a place in a jazz master, but amplifying this side-channel would no doubt create a somewhat unnatural sound if done to a good extent.

With that in mind, most equalization that occurs during a jazz mastering session is corrective and isn’t or shouldn’t be used to accentuate frequency bands. Most accentuation will be too excessive and detract from performance.

What Jazz Albums to Listen to if You Want to Master Jazz

If you’re curious how your jazz master should sound, take a listen to some of these references first:

- Mingus Ah Um by Charles Mingus

Moanin’ by Art Blakey* Headhunters by Herbie Hancock

- A Love Supreme by John Coltrane

- Sunday at the Village Vanguard by Bill Evans

Each of these albums can serve as a great reference for a good jazz master. Listening to all of them critically should give you a comprehensive understanding of what makes a jazz record unique.

This is a great Jazz album to listen to if you want to familiarize yourself with Jazz and Jazz production.

If you do choose to listen to these records, pay particular attention to the stereo imaging, the dynamic range, the frequency spectrum , and the clarity of the instruments. By doing so, you’ll notice how little these tracks are processed, and why that is.

In truth, and as I’ve stated throughout this post, the intention of jazz and jazz recording is not to create something that is unrealistic or unnatural in its delivery. A jazz recording is meant to sound as if you were listening to the performance live, in a well-treated studio (as this is how many of the greatest jazz records were recorded).

With that in mind, you should be able to hear each instrument clearly and feel the space that exists between them.

This is why you should avoid over-compression, excessive harmonic distortion, and excessive equalization when mastering a jazz record. You want to avoid unnecessary masking, distortion, and an unnatural frequency spectrum at all costs.

When mastering a jazz album ask yourself, does this sound like I’m in the room with the musicians, sitting in the best spot of the studio? Or does it sound like a processed recording?

Hopefully, the answer is the former.

In addition to listening to jazz albums, it may be helpful to contrast mastering jazz with mastering other genres. With that in mind, here is a blog post about mastering rock music:

With it, you’ll be able to recognize the primary differences between mastering to create a specific sound, and mastering to retain the intention of the original recording.

Conclusion

When mastering jazz music, oftentimes, less is more . Mastering jazz is more about what you shouldn’t add to a mix than what you should, and for that very reason, it is possibly the easiest genre to master incorrectly.

As mastering engineers, we often want to validate our role in the production process, as if to say ‘I’m here! I made my mark on this album.’ But when mastering jazz, it should feel as if you were never even there at all.

With that said, let’s summarize what to avoid when mastering a jazz album and why.

Compression:

Compressing will lead to masking, or a blurring between instrument groups, resulting in a lack of clarity. This clarity is crucial as it allows for each instrument to be heard and appreciated.

Furthermore, it lessens the dynamic range. Dynamics are a crucial aspect of jazz and can be considered almost an instrument in and of themselves. Reducing a jazz mix’s dynamics is like cutting the notes out of a saxophone performance. It simply shouldn’t be done.

Distortion:

Although a little harmonic generation can be a great thing, a little goes a long way in jazz. Just like the dynamics, the silence or “space” between instruments is incredibly important.

If you introduce significant harmonic distortion, you will make the recording sound full. Granted, a “full” sound is sought after in most genres, but in jazz, it means that the valuable asset of silence is lost.

Equalization:

Jazz recordings and jazz performances are carefully orchestrated to include instruments that cover the frequency spectrum in a desired and intentional way. By amplifying or attenuating frequencies in a significant or excessive way, you are essentially claiming that the orchestration chosen by the artist wasn’t correct.

In this regard, you aren’t respecting the artist’s intention. That being said, you should only equalize when necessary, and only to emphasize and accent aspects of the instrumentation in a subtle manner, or to correct problem frequencies.

If you’d like to hear how your music would sound mastered without committing to an engineer or studio first, send us a mix here:

Are you a Jazz Musician or a Mastering Engineer interested in Mastering Jazz?