Analog vs. Digital Mastering

Quick Answer

Analog mastering is the process of using analog equipment to process a signal to prepare it for distribution; digital mastering is the process of using solely digital processors and software to process a signal and for the same reason. Analog mastering and digital mastering have their respective benefits and drawbacks.

Analog vs. Digital Mastering in Detail

There is often debate as to which of the dominant forms of processing audio is better; however, each form of processing offers certain characteristics and quirks that make them more suitable for a specific job.

Both analog and digital mastering can work well given the situation at hand.

If you’re looking to determine which form of mastering is best for you, and in turn which one may be better for the specific music or mixes you’re creating, you’ll first have to explore what makes each mastering type unique.

Which form of mastering is "Best" depends on the issue you wish to solve at a given time.

For example, you’ll have to understand how and why mastering with analog equipment can often create a fuller sound, or how and why digital mastering allows for more accurate and precise changes. In the process, if you had any inclination or leaning toward one or the other, perhaps understanding each form of mastering will give you a greater appreciation for both.

Whether you're a musician or an engineer, understanding these forms of processing can help you have a better appreciation for both, and for mastering.

All this to say that although one form of mastering may be better for you, saying it is the better form of mastering overall would be a statement most likely based in prejudice - so instead of doing that, let’s look at specific situations, and determine based on the merit of each form of mastering and their specific natures, which form of mastering would be better for that given situation.

Saying one form of mastering is overall better than the other is most likely incorrect, or slightly biased.

With that said, we’ll be looking at specific issues you may face as an artist or an engineer, explaining why these issues may be occurring, and then determining how they can be remedied with each form of mastering.

These examples of specific issues are:

- My mix or master sounds weak or too thin

- My mix or master lacks definition and clarity

- My mix or master is not loud enough

- My master sounds distorted in an unpleasant way

Hopefully, by looking into these specific issues, and determining how and why one form of mastering would be better suited to solve that issue, we can determine which form of mastering will work better for you and your needs.

Some of the issues you may face as an artist while trying to get your music mastered are covered here.

In this process of doing so, let’s keep a focus on the technical aspects so that we can understand how each form of mastering may also be better suited for similar issues not addressed here.

If at any point, you’d like to hear how an analog mastering session would work for your mix, you can send it to us here:

This way, you can hear how analog processing affects a signal, and perhaps better understand some of the information presented in this article.

And if at any point you are curious as to how one form of mastering may work with an issue specific to your music or mix, and it isn’t detailed here - feel free to reach out to us over social media, and we’ll respond as soon as possible.

My Mix or Master Sounds Weak or too Thin

This is a common issue with mastering. You listen to your mix or master, and then to a popular one online, and notice large discrepancies between the two.

Often, a master may not hold up when compared to other masters of a similar genre.

Why does your master sound small, while theirs sounds grandiose and full? Although there may be a few different reasons for this, a thin-sounding master is often a telltale sign of lacking harmonics.

But what are harmonics?

Harmonics are amplified frequencies that always relate to the fundamental of a recording, in that they are multiples of this original fundamental. Harmonics enhance a recording by making the fundamental more easily perceived, as well as bringing complexity to an instrument, mix, or master.

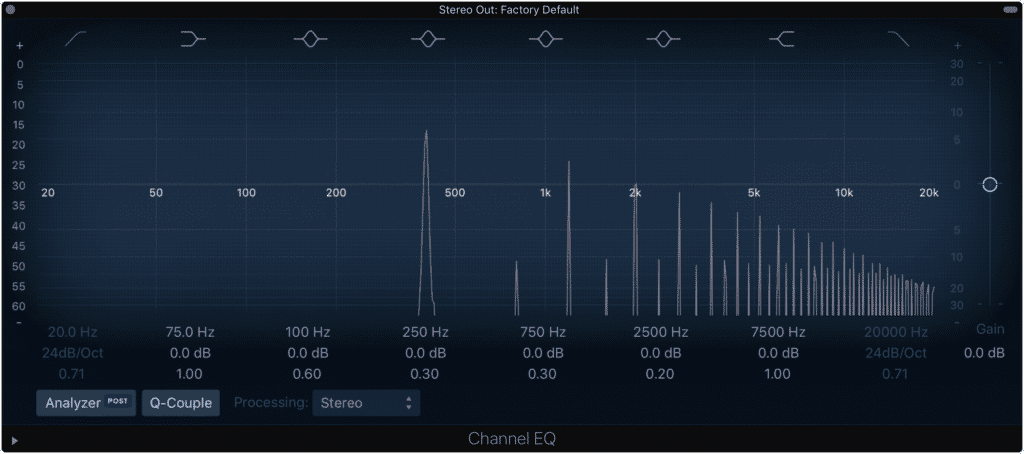

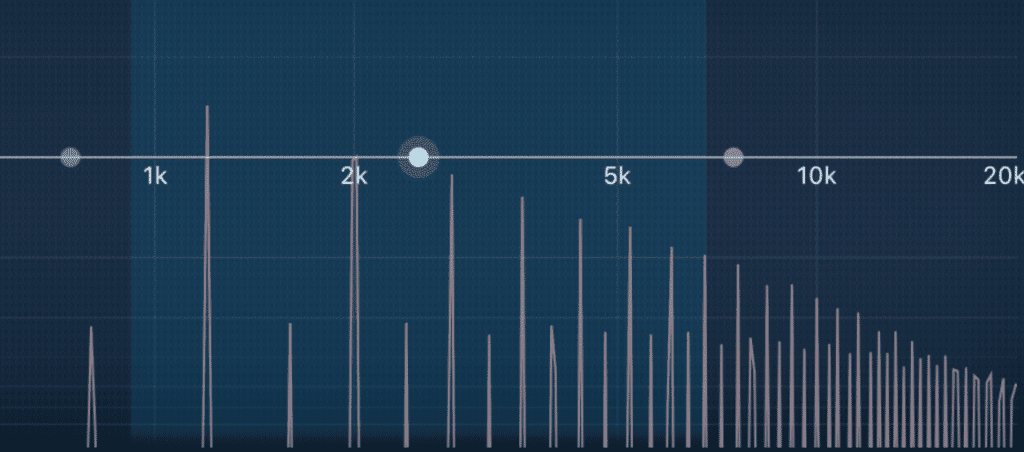

Notice the harmonics decreasing in amplitude after the loudest and lowest frequency fundamental.

But how and why do harmonics add complexity, and why do they make a mix or master sound full as opposed to thin?

Well, think of it like this. You have your original recording, with all of its various instruments, sounds, and vocals.

Various instruments are used to cover the full frequency spectrum during the recording process.

Each instrument falls into the frequency spectrum in a specific way. For example, your kick and bass occupy primarily the lower frequency ranges, whereas instruments like piano or vocals, can cover a wide range of frequencies all along the frequency spectrum.

The bass guitar is used to cover the lower to low-mid frequencies.

A good composition can be arranged by making use of this - by including various instruments to cover the frequency spectrum in a full-sounding, or if not full, a very intentional way. Because instruments vary in their individual frequency response, when combined, they cover the frequency spectrum, and sound what we often refer to as “full.”

But, sometimes this arrangement isn’t enough - sometimes the instruments used aren’t properly arranged, or if they are, maybe they need some help in filling out this frequency spectrum.

As you can see, harmonics are used to fill out the frequency spectrum.

This is where harmonic generation comes in - a form of distortion in which harmonics can be created to better fill this frequency spectrum and make it sound full.

So how does digital mastering or analog mastering help or hinder this process?

In the late 1980s, early 1990s, adding these harmonics using a digital mastering system would have been difficult. Because distortion, or at least the distortion we enjoy hearing, doesn’t naturally occur in a digital system, you wouldn’t have been able to achieve certain forms of harmonic generation.

In digital processing, harmonics don't occur naturally or without further processing.

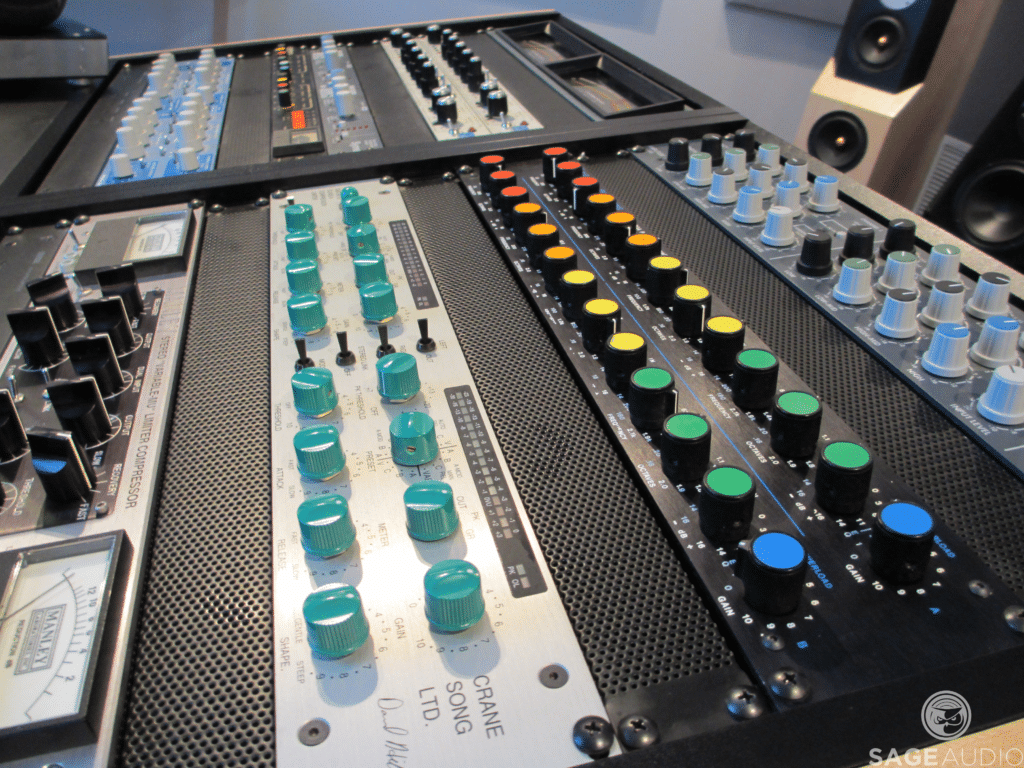

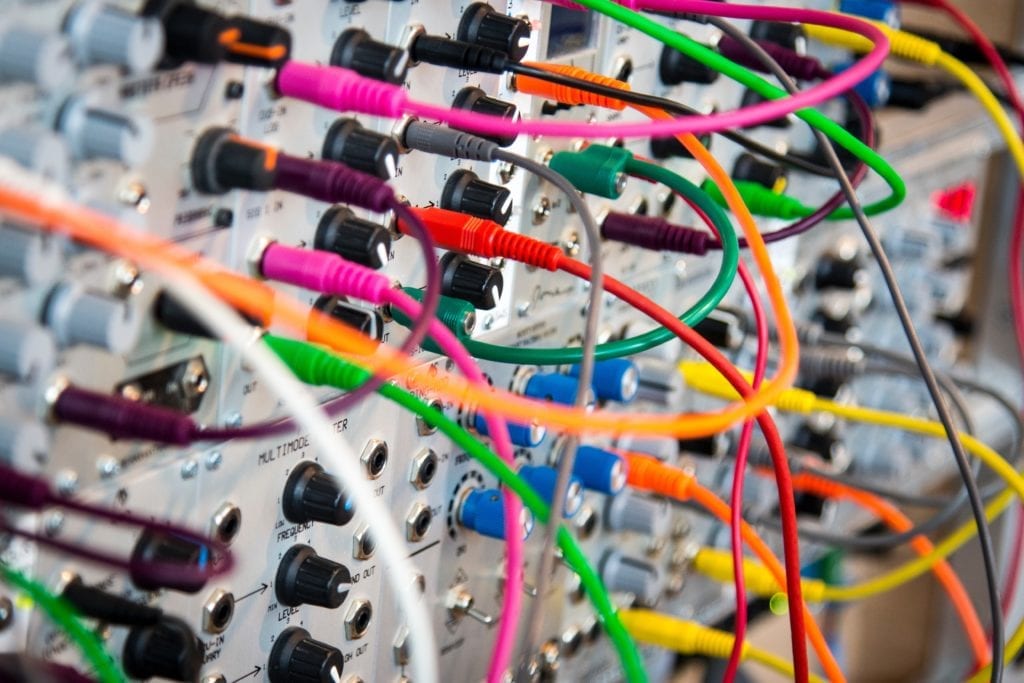

As a result, if you wanted to add harmonics during the mastering stage, you would’ve needed analog equipment. In an analog mastering setup, the very act of running the signal through the analog hardware creates these harmonics, and in turn, fills out the frequency spectrum.

Harmonics occur when running a signal through analog equipment.

With that said, if this article was written during that day and age, the answer to the question, “Which is better for this issue?” would’ve been a clear cut “Analog Mastering” - but digital processing has certainly come a long way since then.

As the power of computers has grown exponentially, and the coding behind digital processing has become more complex and useful , harmonic generation has become an option for digital mastering.

In fact, if you’ve ever used an analog emulation plugin, be it a digital model of a Studer tape machine, or maybe a digital variation of a Universal Audio LA-2A compressor, you’ve added these harmonics into your signal.

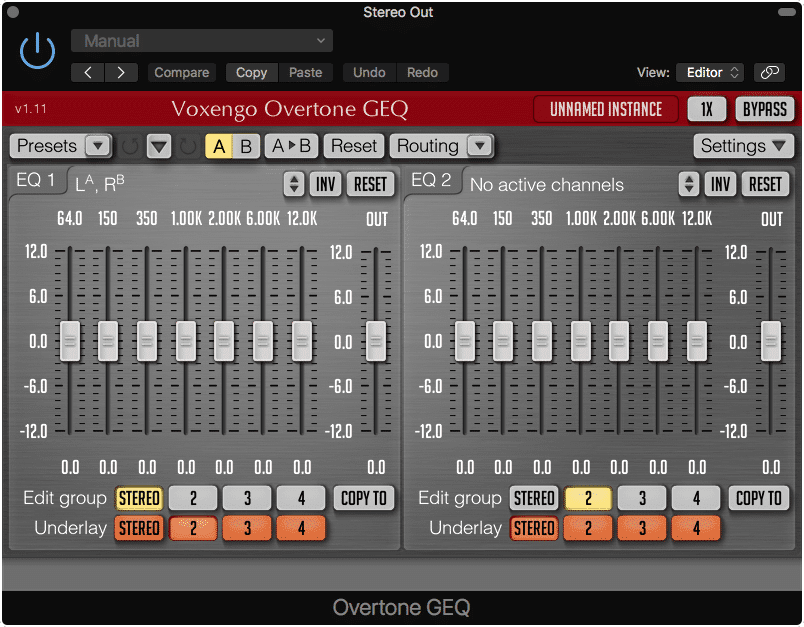

This free Voxengo plugin is used to generate harmonics in a digital system.

Now, although this emulation can occur in a Digital system, and harmonics can now be added during digital mastering, it should definitely be noted that the nature of a piece of analog equipment is much more complex, detailed, and nuanced than can currently be coded into software.

Although many digital emulations sound great and offer an easy way to quickly add harmonic generation, analog mastering still offers the harmonic complexity that digital is currently incapable of offering.

So, all things considered, if your mix or master is sounding thin, the best option is Analog Mastering.

If you’d like to learn more about harmonics and harmonic generation, check out our video that delves into how to add, and measure harmonics.

My Mix or Master Lacks Definition and Clarity

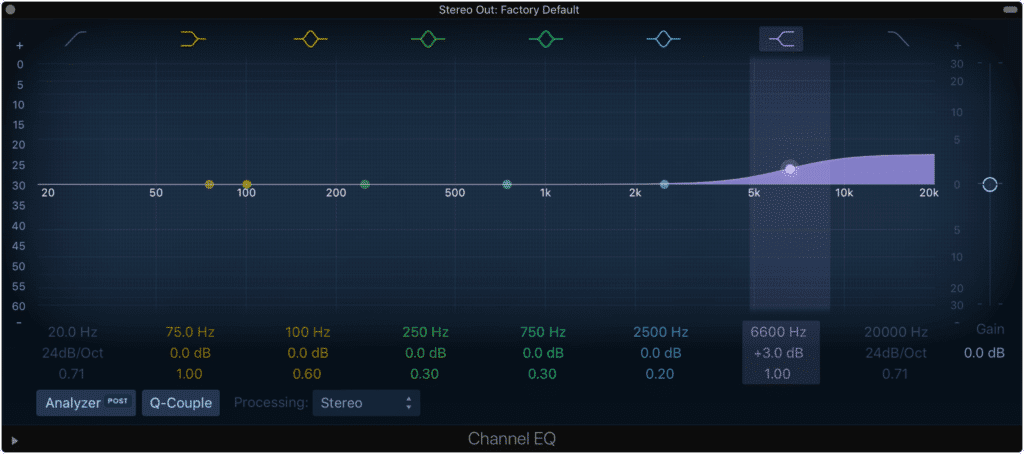

To many, the quick and easy remedy for this issue would be to add a shelf filter during equalization and amplify the higher frequencies of the mix. True, this can be a way to accomplish greater definition and clarity, but it often doesn’t address the actual issue at hand , nor does it offer us any greater understanding as to why this may be happening.

Inserting a shelf filter may alleviate some issues with an unclear sounding master, but it doesn't get to the root of the problem.

At the later stages of a song’s production , maybe during mixing, or after mastering has been accomplished, the amount of processing used has become significant. This can be a good thing, meaning this processing has benefitted the sonic characteristics of the original recording - or it can mean that the song was degraded using unnecessary processing.

If you find yourself in this position, in which your mix or master lacks definition and clarity, it may mean that excessive compression was used, and used in a manner that causes this lack of definition and clarity.

Often, too much compression has caused this lack of clarity.

How Can Compression Reduce Sonic Clarity and Definition?

Compression in its most basic form is the attenuation of louder dynamics. When these dynamics are compressed, the transients of the instrument or instruments being compressed may also be compressed and attenuated, making them less perceivable to the listener.

Because transients offer the sonic detail of an instrument, and are often the identifying indicator as to what instrument is being played, removing or attenuating these transients can have a negative effect of a mix or master.

What Compressor Settings Result in a Lack of Clarity and Definition?

A quick attack and a slow release time will cause a compressor to work sooner, and continue to attenuate a signal for longer. This means that transients, which occur as soon as a sound begins, will be attenuated.

A quick attack time means the compressor kicks in sooner and begins to compress the signal almost immediately.

With that in mind, a longer attack and shorter release time are needed when mixing and mastering, if you want to keep these transients intact. By setting an attack time longer than your transient, and a release time short enough to return the signal back to its relative unity quickly, a compressor can be engaged without attenuating the transient, and without capturing other unrelated transients.

Subsequently, a recording retains its clarity and detail.

But, what does this have to do with Digital and Analog Mastering?

In a digital system, achieving shorter attack and release times is easier to accomplish. This is because the signal being processed is a strictly digital one, which can be processed on a binary level.

When working on a binary level, quicker attack and release times are easier to accomplish.

Typically in a digital system, you can achieve attack times of less than 1ms, and release times of less than 5ms.

In digital compression, an attack time of less than 1ms, and a release of less than 5ms is possible.

When mastering in an analog system, you’re working with an electrical signal, and affecting that signal with physical components. This makes it much more difficult to achieve incredibly quick attack and release times.

In an analog set up, electrical components are being utilized, resulting in slower attack and release times.

Typically in an analog system, you can only achieve attack times of no lower than 10ms, and release times of no quicker than 50ms.

In analog mastering, the attack and release times are slower.

Now, as you can imagine and as well addressed above, not being able to set a quicker release time would result in more unrelated transients being compressed, which could, in turn, result in a lack of clarity.

With that said, if clarity, detail, and transient retention are of utmost importance, your best bet is using Digital Mastering.

If you’d like to learn more about compression, and how it relates to mastering, check out our blog post here:

It shows how a compressor is used during a mastering session, and how the attack and release times affect the transients of a master.

My Mix or Master is Not Loud Enough

Although there are many opinions regarding mastering and loudness, let’s suspend those for a moment and just admit that achieving a certain loudness can be a big part of the mastering process.

In fact, if an artist wishes to achieve a certain loudness, just so long as it is within reason, it’s a mastering engineer’s job to try to accommodate and respect the wishes of the artist. With that in mind, creating a loud enough master - one that can compete with other masters out at the moment, is something to understand and try to work through.

Creating a loud master can very much be a part of the mastering in general.

How does Loudness Relate to Analog and Digital Mastering?

In short, loudness is achieved by amplifying the signal, while to the best of the engineer’s ability, not causing distortion. Doing so often means compressing particularly loud dynamics so that the overall signal can be amplified and result in an overall perceived greater loudness.

Considering this compression and limiting can be accomplished with either analog or digital equipment, one doesn’t have a clear advantage over the other; however, there is one aspect of analog mastering that should be taken into consideration.

Both analog and digital mastering work well when trying to make a master sound loud.

When mastering, loudness is always considered or thought of as loudness before distortion. Of course, you can push the signal into greater perceived loudnesses by distorting it, but this is definitely not ideal and almost goes without saying, widely avoided.

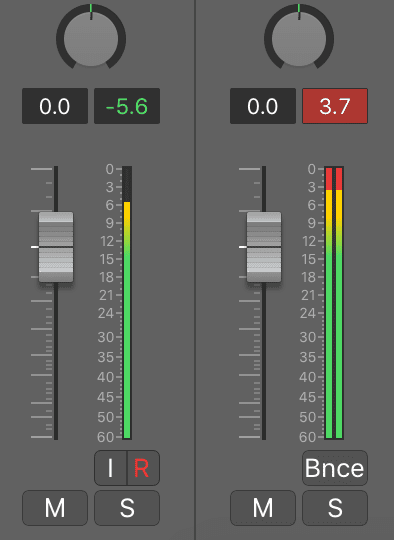

In a digital system, 0dBFS means you have no more headroom before distortion will occur. You can push the signal farther, but it will distort.

In an analog setup, 0VU is not the cap in terms of headroom.

In an analog system, 0VU doesn’t mean there is no headroom above it - the amount of headroom is often an additional 20dB above 0VU. This isn’t to say that the analog setup is 20dB louder than the digital, just to say that the headroom of an analog system is relative to the calibration.

When it comes to how much signal can be sent through an analog system without distortion, many factors come into play. These include but aren’t limited to, the overall wattage of the amplification system, the components used in the analog equipment, and, as it relates to the engineer monitoring and accessing any distortion in the master, the speaker system.

This means that analog systems don’t have as much of an absolute cutoff as digital systems do. Regardless of how loud a signal can become in an analog mastering setup, it will inevitably need to be made into a digital signal for the sake of distribution - so when it comes to trying to achieve greater loudness, either analog or digital mastering will work well.

Since any analog signal will need to be converted back to digital, again either analog or digital mastering works well for creating a loud master.

If you’d like to learn more about achieving a greater perceived overall loudness, take a look at our blog post on the topic:

It shows how certain techniques can be used to enhance your mix and to make them sound louder and more upfront.

My Master Sounds Distorted in an Unpleasant Way

This issue is very much related to the one discussed just prior to this one, so if you skipped it, perhaps read it prior to this section for a better understanding of the factors involved.

To reiterate, distortion , as it relates to mastering, is often tied to headroom. When a signal is pushed past the available headroom, the signal then becomes distorted. This distortion looks different in a digital than an analog system.

When pushed past 0dBFS in a digital system, distortion will inevitably occur.

When a signal is pushed past the 0dBFS limit of a digital system’s headroom, the distortion type that occurs is often referred to as clipping. Clipping distortion is the generation of easily perceived high-order harmonics, which occur where our ears are most sensitive.

These harmonics are often unpleasant and shrill, resulting in a less than desirable listening experience. So, if you were attempting to achieve a loud master, and by doing so pushed the signal into clipping, you may have wound up with a master that sounds distorted in an unpleasant way.

What Happens during Analog Distortion?

During analog-based distortion, the harmonics that are generated are typically of a lower order, meaning they don’t occur where our ears are most sensitive. If these harmonics are loud enough they can become unpleasant, but at lower levels, these harmonics can add complexity to a mix.

So if you’re experiencing a master that seems to be distorted in an unpleasant way, perhaps try analog mastering to find out if that helps.

If you’d like to hear your mix mastered with analog equipment, send it to us here:

We’ll master it for you and send you a free mastered sample for you to review.

With that said, if your master is distorted in a negative way, it may be because of digital clipping. In this case, you’ll either need to find ways of avoiding digital clipping or choose analog mastering.

Conclusion

Deciding which form of mastering is best for you, truly depends on the current status of your mix or previous master, and how you want to proceed. There are certain situations that call for digital mastering, and ones that call for analog mastering.

With that said, there is no objectively better form of mastering - just ones that are better at remedying specific issues or provided a certain desired sonic characteristic.

Choose the form of mastering that works best for your music or production style.

Before deciding which is best for you, consider what you’re trying to achieve with your mastering process, as well as what you don’t want. When you know these things, you’ll know which form of mastering is best for you and your project.

If you’d like to hear your music mastered using analog equipment, you can always send it to us here for a free mastered sample of your mix:

This way you can be certain, which form of mastering is best for you.

Do you prefer analog or digital mastering?