What is Mastering for Vinyl?

Mastering for Vinyl Quick Answer:

Mastering for vinyl is the process of creating a separate master that can be cut into a vinyl record without added unwanted distortion. It consists of a mono stereo image up to 150Hz, a tamed high end, and if needed, a track listing that is consistent with the frequency limitations of record cutting.

Mastering for Vinyl in Detail:

With the resurgence of vinyl records as a popular way to listen to albums, many artists have seen an opportunity for a new stream of revenue.

In turn, this has transformed the often ignored art of mastering for vinyl, and vinyl cutting, into a topic of popular discussion amongst artists, and audiophiles alike.

After nearly a decade of steady sales, it seems the vinyl record is here to stay.

In the midst of this conversation has emerged an important question: What is mastering for vinyl?

This question is often followed by another: Do I even need a separate master for vinyl?

In short, the answer to the latter question is yes. Although many artists have elected to use their digital masters for the vinyl cutting process, the results are often mixed in terms of quality.

Depending on the master, some of, or all of these issues can occur when using a digital master for the vinyl cutting process:

- Varying degrees of distortion

- Skipping needles during playback

- Lacking dynamics

- An overall less pleasant listening experience

Although some vinyl cutters are more than willing to take a digital master, and make adjustments as they see fit, many request a vinyl specific master.

Also, when you consider that you will be unable to hear, approve of, or change any alterations made by a vinyl cutter prior to the actual cutting of the disc, it may be best to implement these changes during the mastering process.

With that said, if you are considering distributing your album in the form of vinyl records, you should absolutely have a secondary master. Make one that was created with vinyl cutting and reproduction in mind.

What is the Difference between a Digital and a Vinyl Master?

The best way to answer this question, is to understand the differences between the digital and vinyl mediums.

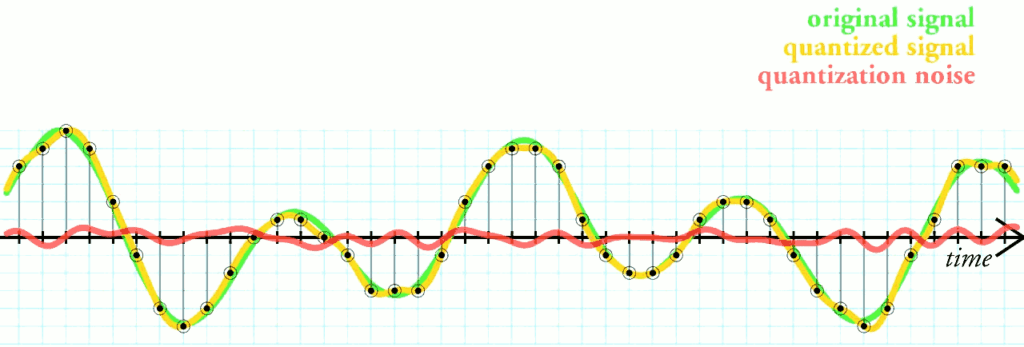

It goes without saying, the digital and vinyl formats are completely different in terms of their mediums and storage capabilities. In a digital format, analog signals are converted into digital information by means of quantization and sampling.

From a digitally stored file, these samples are converted back into an electrical signal, and then lastly perceivable sound waves generated by a speaker system. This process is virtually identical every time, with errors or artifacts only occurring with the purposeful degradation of a digital file type from lossless to lossy.

Quantization, or bitrate distortion can occur if the bit depth is truncated without dithering to mask the noise it generates.

The digital medium can store information almost perfectly. It’s only limitation resulting from the storage of dynamic information (quantization) and frequency information (sampling rate).

Even these have been optimized in a digital system, to expand far past the range of human perception.

There is almost no limit to what can be stored in a digital domain. The only limitation here is the playback system (the speaker system) and our ability or inability to perceive vast dynamic ranges and ultrasonic frequency responses.

Although you may already be familiar with the workings of a digital system, it is important to think about how it differs from the physical and limited medium of the vinyl record.

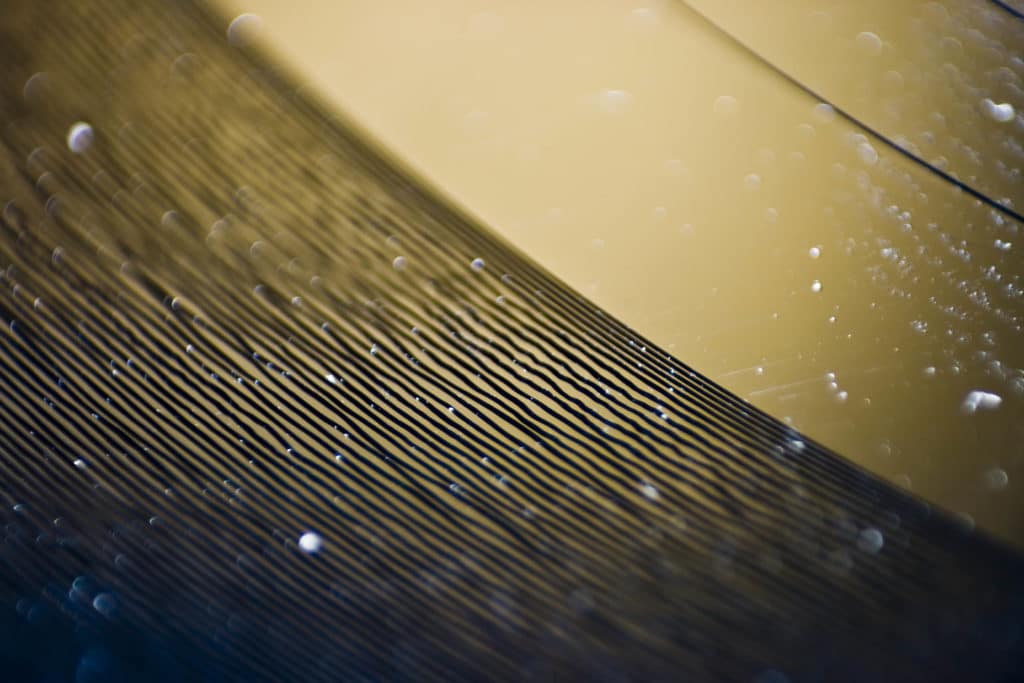

The vinyl record is by its very nature, limited. It is limited in its ability to record certain frequencies.

It's limited in the amount of information it can store, and even limited in it’s ability to record and reproduce complex imaging, beyond that of traditional acoustics.

The nearly perfect quantization and sampling implemented in a digital system is replaced by vertical and horizontal cuts performed by an electrically fed needle.

This begs the question, how could a digital master, designed for a digital system, characterized by an entirely different recording and storage process, translate well onto a limited physical medium?

Often times it doesn’t.

The nature of the two mediums are vastly different - therefore the master needs to be different, if you intend to fully embrace the vinyl medium for what it is.

The Physical Limitations of a Vinyl Record:

The secrets of mastering for vinyl lie in the specific limitations of the physical vinyl record itself, and the cutting process used to create it.

Let’s address the potential issues stated above. Again, they are:

- Varying degrees of distortion

- Skipping needles during playback

- Lacking dynamics

- An overall less pleasant listening experience

Varying Degrees of Distortion:

When is comes to vinyl record cutting, a general understanding of the physics behind the process is needed.

I won’t be exploring the science too deeply, since the information is vast, complex, and may not directly help answer the questions posed earlier.

So here briefly is an explanation as to how the potential for future distortion occurs during the cutting process, and how that distortion occurs during the playback process.

First it must be understood that the physical shape of the vinyl disc causes a varying rate at which the information can be cut into it.

The circumference of the record is great along the outside, than on the inside.

In other words, when a record is being cut, and also during it’s playback, the greater circumference of the outside of the record allows for a greater surface area to be cut.

Since the lathe, and playback system rotate the record at a unchanging rate, and the surface area becomes smaller the closer to the inside of the record the needle gets, the velocity of the needle slows down significantly.

On the outside of a record, the needle or lathe’s cutter moves at roughly 20 inches per second. But on the inside, the needle or lathe moves are roughly 8 and 1/2 inches per second.

Sonically and technically, this would be very similar to reducing the tape speed of a tape machine from 15 ips to about 3 and 3/4 ips.

Notice the speed functions on the lower right side of this tape machine.

In a more modern example, this is similar to reducing the sampling rate of a digital recording from 96kHz to 22.05kHz.

In all of these examples, you’d be able to notice a significant decrease in the replication of the high end or the high frequency range.

This is precisely what happens to a vinyl record. As the surface area is reduced, the ability to both create and playback high frequencies is significantly reduced.

By the time the lathe needle reaches the center of a record, 15kHz has been attenuated 3dB.

Furthermore, the amount of distortion created during the cutting process, directly corresponds to the amplitude of the high frequency signal at these low surface area, inner record parts.

Because the surface area is limited closer to the center of the record, the lathe must work harder to cut higher frequencies. If the needle works too hard, it will jump out of its groove, causing hissing and distortion.

Due to this physical limitation, it is imperative that the level or amplitude at which the record is cut be closely monitored, and uniform across the entirety of the record.

This is why the track list of a vinyl record needs to be carefully planned.

Typically, softer tracks with a lower integrated amplitude are placed closer to the center of the disc, while the louder more aggressive tracks are sequenced farther to the outside.

Again, the additional surface area along the outside of the record allows for more information to be cut without resulting distortion.

The smaller surface area, and subsequent cutting speed of the center, lends itself to increased distortion at high amplitudes.

So, how Does this Relate to a Digital Master?

As we’ve just seen, distortion can occur on a vinyl record when the amplitude of high frequencies is too prevalent.

This of course, is not an issue when transferring information into a digital medium.

The fact that a digital medium can handle a greater amplitude of high frequencies is often exploited and used.

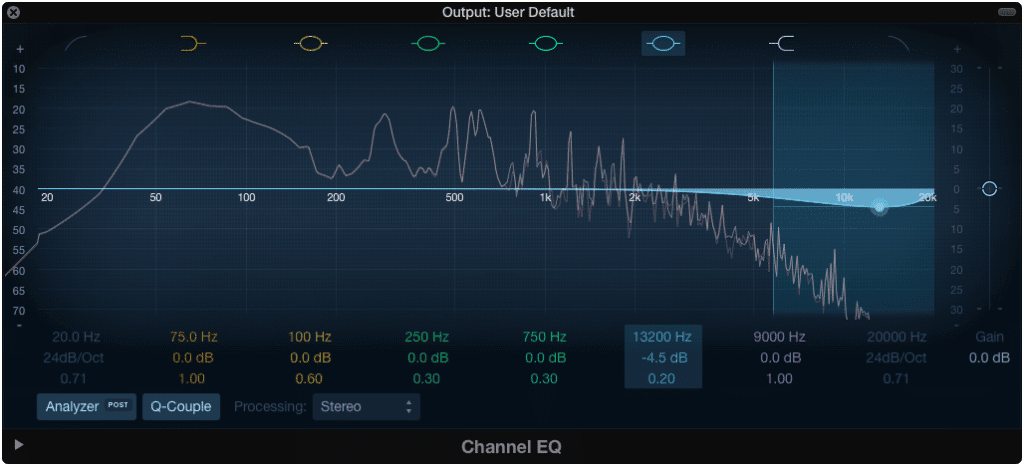

The equalization curve of a mix, with an accentuated high frequency range.

For example, hip-hop and rap is often characterized by its emphasis on the higher frequencies. This occurs in both the instrumentation, and the equalization of the vocal performance. It’s no coincidence that this new frequency standard was only implemented after the popularization of the digital medium.

An accentuated high frequency range is not exclusive to hip-hop. It can be found in almost any genre today. This may be because its use is often conflated with high fidelity recording.

Because these frequencies are not only acceptable, but favorable within the digital medium, a digital master is most likely to include them.

All this to say, that if a digital master with an accentuated high frequency range is used during the vinyl cutting process, it will no doubt cause unwanted distortion.

Skipping Needle During Playback:

A 24 bit recording holds the potential for 144dB of dynamic range. A vinyl record on the other hand, only has about 55dB to 65dB of dynamic range.

This is clearly a significant difference, but what does this have to do with needle skipping?

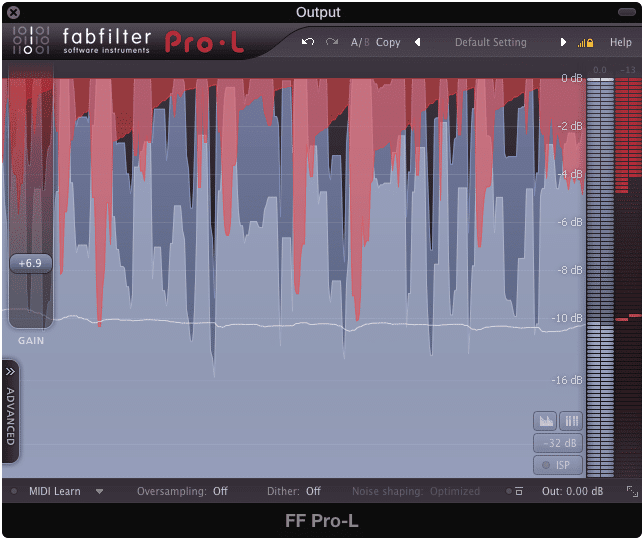

As many of us know, in a fair amount of digital masters, the dynamic range is typically limited. This is due to excessive “brick wall” limiting techniques, aimed at achieving overall louder playback.

Excessive brick wall limiting is common in digital mastering, although this is an extreme example.

But in some instances, perhaps between songs, or song sections, a digital master can go from a very low level of playback, to a very loud one.

In the digital medium this is no issue. In a vinyl medium, such a dramatic increase in volume can cause skipping.

Because a vinyl record is created by cutting grooves into a disc, a dramatic increase in volume will result in a dramatic cut.

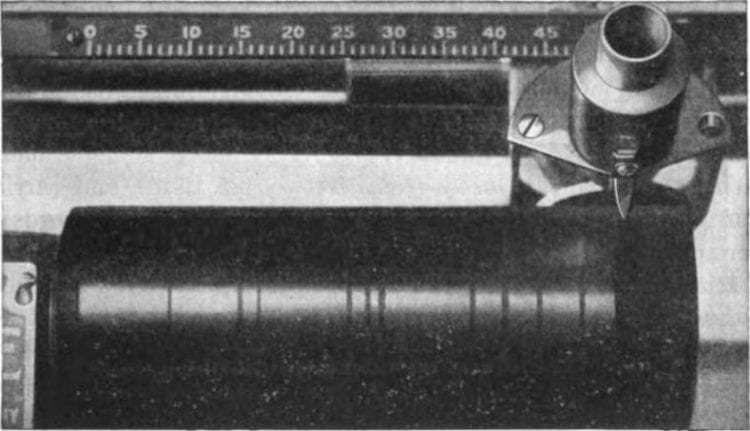

Wax cylinders preceded the vinyl record. Lateral movements recorded sound waves similar to how the inner ear functions.

When the needle of a record player is tracked along this cut, the bump can cause the needle to kick. This causes the needle to exit its intended groove.

This problem is only exacerbated on the outside of the record. A greater needle velocity increases the likelihood of this occurrence.

If an artist or mastering engineer intended for a large increase in volume, a compromise would need to be reached before transferring the song to the vinyl medium.

Of course if the only version available is the digital master, this dynamic compromise will never be made, and the vinyl will most likely skip as a result.

The other alternative, is that the vinyl cutter will recognize and adjust for this volume differential, by decreasing the overall dynamics of the track using compression or mormalization. This increased compression or normalization will result in the opposite of the original intended effect.

The needle can also skip when high energy low frequencies are out of phase. Although this is easier for the vinyl cutter to fix without causing a noticeable difference is sonic characteristics, it is still wise to fix this before the cutting process.

Lacking Dynamics:

“Brick wall” limiting is often used in digital mastering. It allows for the integrated volume of the track to be louder, but results in truncated dynamics and transients.

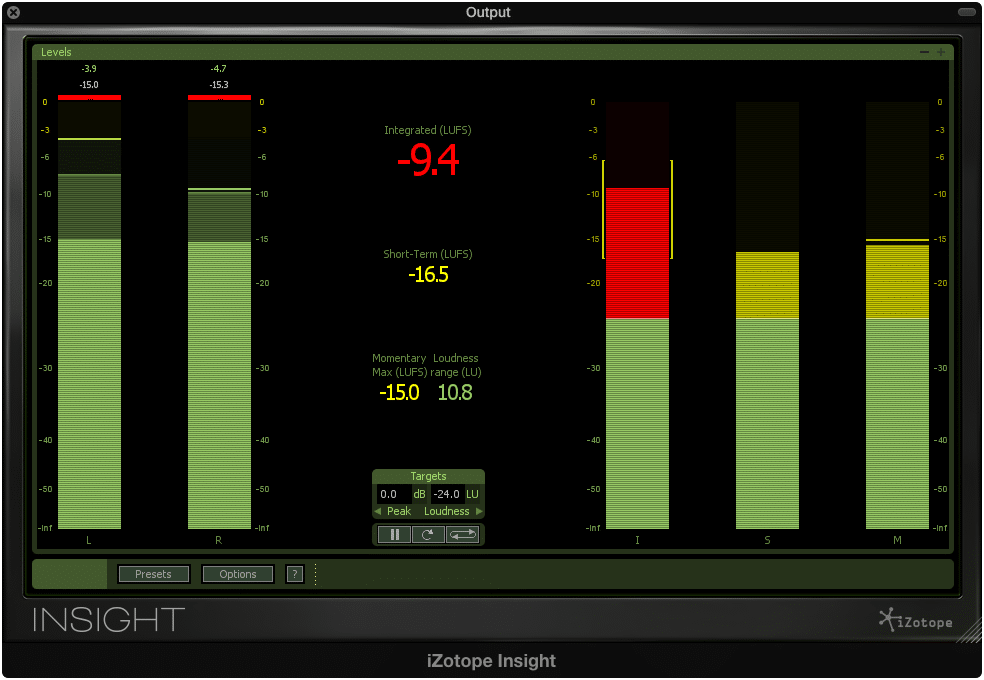

An integrated LUFS of -9 isn't uncommon for a digital master.

Fortunately, the very act of transferring a digital master onto a vinyl record can restore some of the dynamics and transients lost during the original mastering for digital process.

This isn’t ideal however, as it doesn’t take advantage of the full dynamic range of a vinyl record.

Furthermore due to the afore mentioned physical limitations of both the vinyl record and the lathe, excessively limited and loud signals will overwhelm both, and cause distortion.

In order to avoid this distortion, vinyl cutters will often reduce the volume of master, resulting in a severe limiting of the original dynamic range.

An Overall Less Pleasant Listening Experience:

This is essentially the combination of the prior three potential issues; however, their cumulation provides one of the more interesting and rarely discussed issues in modern vinyl cutting.

As one can imagine, overtime lathes have improved. Meaning they can handle more intense amplitudes without causing a cut that will universally distort.

The keyword here being universally.

Although lathes can handle the creation of higher amplitude vinyl records, that does not mean that most consumer models can handle them during playback.

The playability of a record was once a huge area of concern for manufacturers and labels alike - so much so that they created regulations for vinyl cutting, designed to ensure the adequate playback of vinyl records across even the most basic of consumer devices.

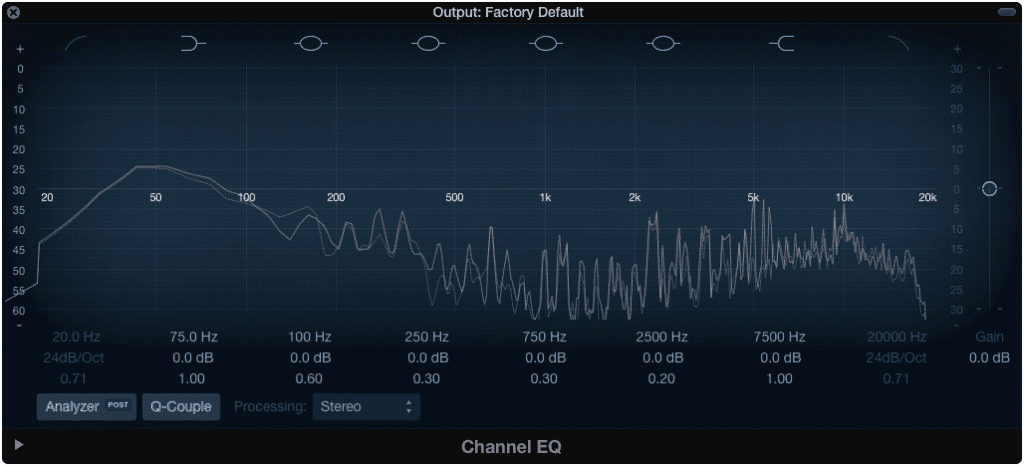

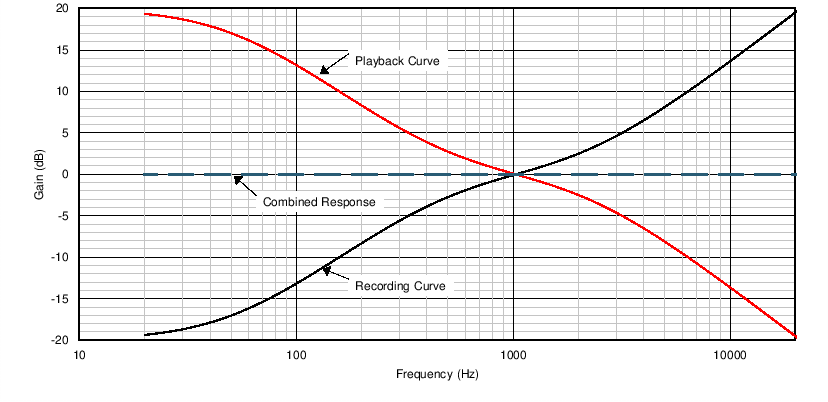

An emphasis and de-emphasis equalization technique is used to ensure playability across various consumer equipment.

As vinyl records changed from being the most prominent musical medium, to more of a niche, these regulations fell to the way side.

Today, digital streaming platforms are the primary distribution method for music.

When vinyl cutters use a digital master, with its increased amplitudes, low end phasing issues, and overall more demanding specifications, it may not reflect negatively on their systems during playback.

But on consumer grade turntables, we’ll be stuck with the negative aftermath.

Most consumer turntables aren't equipped to handle high amplitude records.

With all of this information in mind, let’s answer another question.

How to Master for Vinyl?

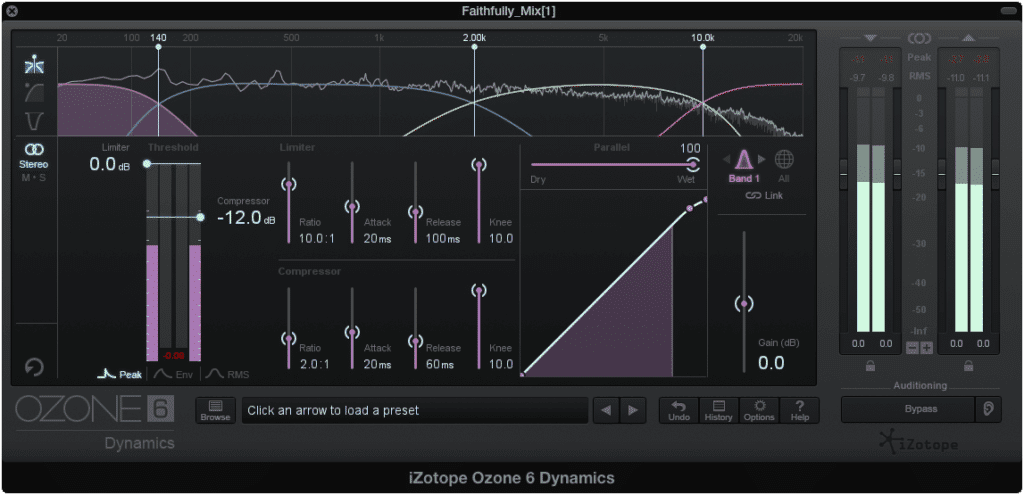

- Control any intense dynamics

Use a multi-band compression instead of a limiter.

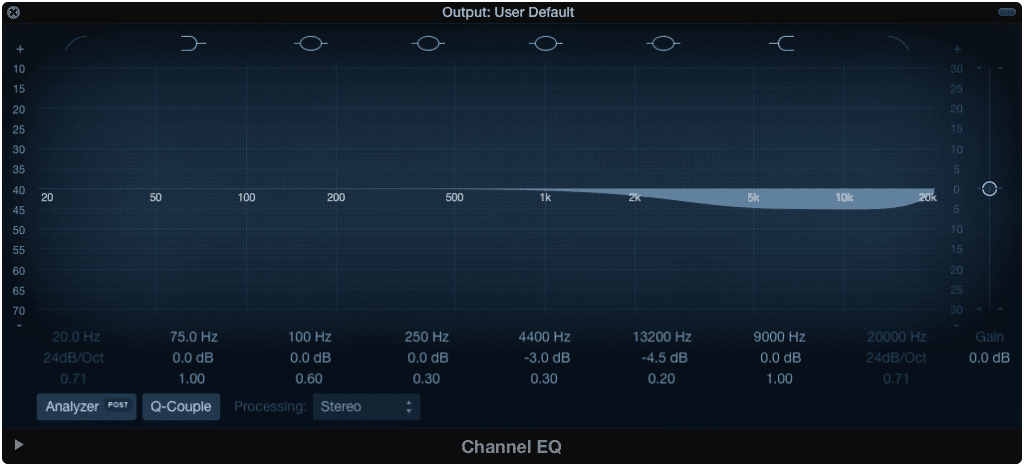

- Attenuate any excessively high frequencies

A basic EQ will work well for this.

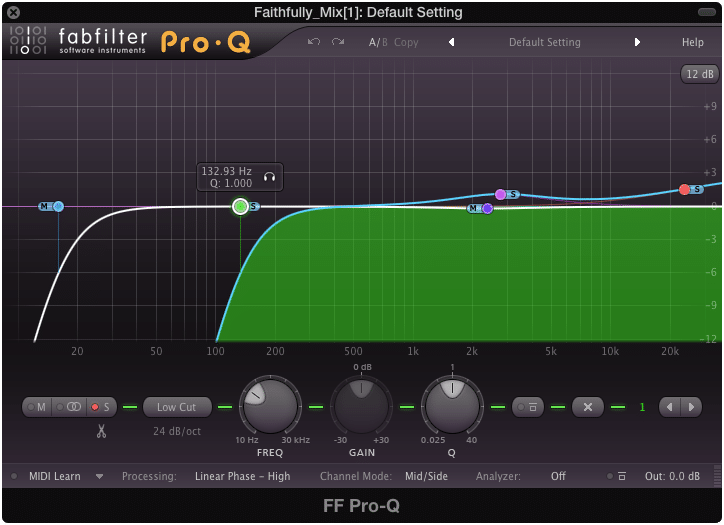

- Center the lower frequencies to avoid phasing issues.

Mid-side processing is best for centering low frequencies.

- Do not use brick wall limiting.

- Do not create an excessively loud master.

- Keep the limitations of consumer grade playback systems in mind.

Conclusion:

Although many claim that a digital master is adequate for vinyl record cutting, there are many reasons why you may want to have a separate master for the process.

It is best to be in control of the sound of your record at all stages. This means not leaving anything up to chance, or neglecting to review any changes made to your record before cutting.

By using a digital master for the vinyl cutting process, you are assuming a great deal of risk.

You are risking that your digital master will not translate well, risking that the vinyl cutter will alter your master in a way that doesn’t drastically change it’s sonic characteristic, and risking whether your record will be able to be played back on a full range of consumer grade turntables.

If you care to see your album properly carried through to its final stages, ensure that it is ready for the vinyl cutting process.

Get your album mastered for vinyl.

Have you ever had a record cut to vinyl?